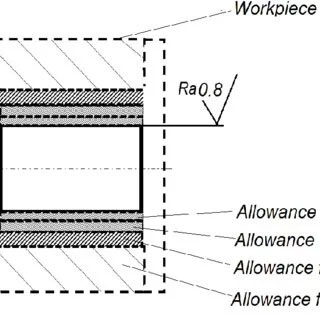

Leaving machining allowances is a professional engineering practice, but how much allowance should be left? The answer to this question is more experience-driven than science-driven. Engineers and technicians consider several factors while calculating the appropriate machining allowances for a part.

The major factors are as follows:

Manufacturing Process

The manufacturing process used to produce the part before machining gives a lot of information on how ‘rough’ it is. Between casting and forging, for example, cast parts are generally less dimensionally accurate and thus commonly require a larger machining allowance of 2-5 mm. For forging, it may be 1-3 mm due to its near-net shape results.

Material Properties

Materials that are prone to dimensional changes or accidents during machining typically require larger machining allowances. Thus, engineers choose to have a higher allowance for ductile materials. Aluminum is more ductile than stainless steel, for instance. Their respective machining allowances for the same geometry may be 1-2 mm and 0.5-1 mm, respectively.

Machining Type

Roughing operations with bulk material removal require larger machining allowances than finishing operations with finer cuts. Take a turbine blade machining operation for example. In the initial roughing cuts on the workpiece blank, the machining allowances are high (3-4 mm), but as the process moves forward and the profile of the blade takes shape, smaller machining allowances in the range of 0.5-1 mm may be used for semi-finishing and finishing cuts.

Tolerance/Finish

Parts with high-quality requirements (tight tolerance, fine surface finish) are typically planned with more allowances to ensure that minor deviations can be corrected during final passes.